SUMMARY

There have been countless controversies in the Star Wars fandom over the years, ranging from the Special Editions to the sequel trilogy.

All these controversies have the same issue in common: audience ownership of the franchise.

This issue causes so much division in the fandom, but these issues all fade with the passage of time.

I’ve been part of the divided and divisive Star Wars fandom since the 1990s, and I’m beginning to realize that every controversy and backlash has been about the same issue. As much as I love Star Wars, the sad truth is that this fandom doesn’t exactly have a great reputation. I’ve watched so many different backlashes over the years, from the controversy over the Star Wars Special Editions to the current controversy over the Disney era.

Oddly enough, one forgotten controversy was what really drew me into the Star Wars fandom in the first place; the death of Anakin Solo in Troy Denning’s Star By Star, a character who isn’t even canon anymore but deserved so much better. Since then, I’ve been on the fringes of so many different backlashes, usually keeping my distance rather than diving head-first into them. Now, all these decades later, I think I’m finally beginning to understand why Star Wars is such a fractured and fractious fandom. It’s because of the issue of audience ownership.

The Dark Times Set The Scene For Star Wars Controversies

A sense of ownership flourished

Let me begin by introducing you to the Dark Times. In Star Wars canon, that refers to the period between the prequels and the original trilogy – the time the Empire ruled the galaxy. But for the fandom, it refers to the time when the Star Wars franchise was essentially dormant. From 1983 through to 1991, Star Wars was largely “over,” and it existed purely in the imaginations of fans who continued to collect the merchandise and play RPGs. It’s so hard for modern viewers, used to a steady stream of Star Wars TV shows and movies, to imagine that era.

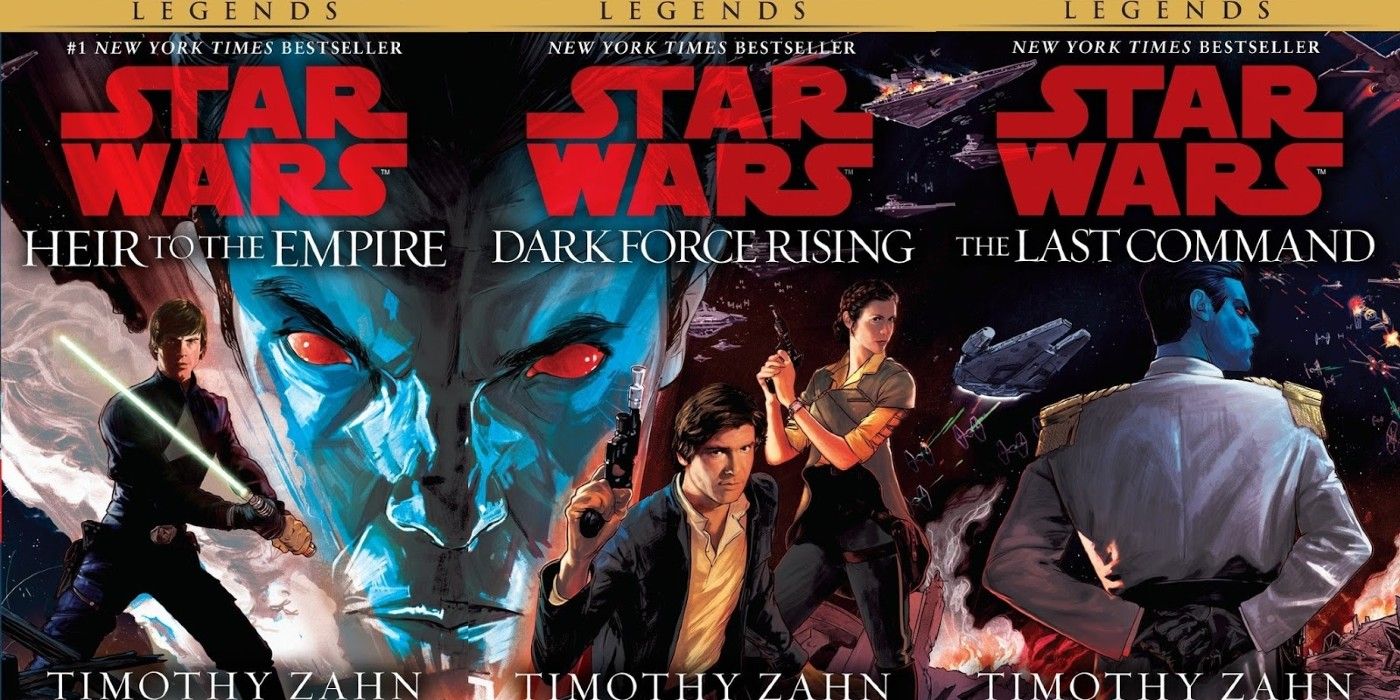

Here’s the thing you have to understand about the fandom back then: because Star Wars existed in the imaginations and storytelling choices of a generation of fans, there was an enormous sense of ownership. Star Wars belonged to them, and they sustained it. Everything changed in 1991, when Timothy Zahn essentially relaunched the Star Wars Expanded Universe with his Thrawn trilogy, and friends who were part of the fandom back then have remembered some frustration even at that early a stage. But the real problems were yet to come.

The Problems Started With The Special Editions

George Lucas vs. the fandom

Who owns Star Wars? For George Lucas, the answer was simple: He did. For Lucas, the imperfections in the Star Wars original trilogy were becoming ever more visible as technology evolved, and he wasn’t happy. In 1997, he began releasing the Special Editions, adjusted versions of the movies that proved massively controversial. He’d continue tinkering for years to come, unable to get some of the changes right, and occasionally backtracking on others.

We’re now so used to the silly internet claim that a reboot or relaunch has somehow “ruined somebody’s childhood,” but it helps to see the Special Edition backlash through that lens. The Star Wars fandom had a strong sense of ownership; now here was George Lucas, dismissing elements of something the fans loved, literally rewriting entire scenes (“Han shot first” being the most prominent example). I remember the Special Editions backlash as a great disturbance in the Force, as though millions of voices suddenly cried out in fury… and they wouldn’t be silenced.

Why The Star Wars Prequel Trilogy Was So Explosive

This wasn’t the story viewers had imagined

George Lucas considered himself to be an artist, and every artist wishes to somehow communicate to a target audience. When Lucas launched the prequel trilogy in 1999 with Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace, he had a very specific audience in mind: kids. Viewers of the original trilogy had grown up with the franchise, and their idea of Star Wars had evolved with them, but Lucas wasn’t aiming at this nostalgic group. He believed Star Wars to be kids’ movies.

Yes, Lucas indulged in light nostalgia, but he never let it overtake the narrative.

This is the key to understanding so many of the controversial story-choices Lucas made at the time. He introduced Anakin Skywalker as a child because he wanted young viewers to relate to Anakin, to enter into his fall and experience it on a visceral level. Ahmed Best’s Jar Jar Binks was comic relief because he thought kids would find him funny. Yes, Lucas indulged in light nostalgia, but he never let it overtake the narrative because he knew his audience – and the fans who’d grown up with the original trilogy, with their sense of ownership, were not his intended audience.

Lucas also had a rather inconsistent approach to the Star Wars Expanded Universe. A recent article elsewhere recently tried to argue that Lucas hated the EU, but that really wasn’t the case at all; after all, he signed off on a lot of it, and adopted ideas such as the city-planet of Coruscant into his movies. Rather, the truth is that Lucas simply didn’t believe he should be bound by it, limited in any way by decisions made by other creators. He was the primary artist, this was his art, and he wouldn’t be restricted by others.

By now, you can hopefully see why this was a conflict of ownership. It was – as the absurd 2010 film put it – “The People vs. George Lucas.” On the one hand, you had a fanbase with a strong sense of ownership, and on the other the creator who insisted he was the real owner. There were other aspects flowing from this as well, of course, issues of racism and sexism, of parts of the fanbase wishing to maintain their ownership and exclude others, but I’ll discuss those complexities in a moment.

George Lucas Sells Star Wars To Disney

The ultimate act of ownership

Lucas remained involved with Star Wars for some years, and the prequel-style controversies continued. Then, in 2012, Lucas sold Star Wars to Disney. There’s a sense in which this was the ultimate act of ownership, a rude reminder to those who had a strong sense of ownership that Star Wars never had belonged to them at all – because here was the creator, selling it to Disney for $4.05 billion. It wouldn’t take Disney long to begin exerting their ownership, setting the scene for further conflict.

Disney canceled Star Wars: The Clone Wars, replacing it with Star Wars Rebels. Just as controversially, they erased the old Expanded Universe from canon, dubbing it “Legends” (a term many found insulting, but which I really don’t think was ever meant to be). From Disney’s perspective, all these decisions were made to allow them to relaunch the franchise. They wanted a relatively fresh jumping-on point for a new generation of viewers, and a way to tell a sequel trilogy without bumping into the canon of untold EU stories.

The Disney Era Became One Of Untold Conflict

It’s Star Wars, but not as we knew it

In 2015, Disney kicked off the sequel trilogy with Star Wars: The Force Awakens. Determined to learn from Lucas’ experiences with the prequel trilogy, the House of Mouse signed off on a movie squarely aimed at nostalgic viewers, but they added new characters as audience surrogates – most notably Daisy Ridley’s Rey, originally an everywoman hero thrust into a galaxy of Jedi and stormtroopers. Finn was marketed not as a stormtrooper-turned-rebel, but as a Black man wielding a lightsaber who actually starred rather than served in the background.

This wasn’t the Luke Skywalker viewers had in mind, the one they’d imagined all these years

The problems really began with Star Wars: The Last Jedi, when Rian Johnson stepped away from nostalgia-bait and dared to subvert expectations. This is most visible with his version of Luke Skywalker, a Jedi Master who had failed and withdrawn from the galaxy because of guilt and shame. Viewed through the lens of ownership, the reaction to Luke’s plot in particular is instructive; this wasn’t the Luke Skywalker viewers had in mind, the one they’d imagined all these years, and they were shaken and angry. They still are, even after an attempted course-correction in Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker.

All this isn’t to defend the Star Wars sequel trilogy, incidentally, which I certainly don’t consider faultless. But there’s a striking amount of vehemence in the way some parts of the fandom discuss the Disney era, and that hints at a much deeper motive than just complaining about poor storytelling choices and inconsistent characterization. It’s because the sense of ownership is offended, leading to a more extreme reaction.

How Racism & Sexism Work In The Star Wars Fandom

Whose Star Wars is it anyway?

How does this sense of ownership fit into the racism and sexism that’s often experienced by so many people within Star Wars? It manifests in an incredibly ugly way, because a vocal minority in the fandom sense that Star Wars is not aimed solely at them, and they resent it. Their ownership leads them to try to force those they object to out of the franchise altogether, explaining why actors like Kelly Marie Train and Moses Ingram received racist and sexist harassment. It’s the darkest side of a fandom.

The latest controversy is over The Acolyte, Leslye Headland’s upcoming Star Wars TV show, and the reasons for the backlash haven’t exactly been subtle. In theory, this show ticks every box for the fandom: it’s made by a lifelong fan, features Jedi and Sith, lightsaber whips that haven’t been seen in live-action since they were created in 1985, and so much more. In practice, YouTubers have gone through every second of the trailers highlighting the absence of white males, there have been accusations of “wokeness,” and quotes from Headland – a gay woman – have been ripped out of context.

Speaking to the New York Times, Headland insisted some of these critics are not part of her fandom at all: “I stand by my empathy for Star Wars fans,” she told them in a text message. “But I want to be clear. Anyone who engages in bigotry, racism or hate speech… I don’t consider a fan.” Headland and I are contemporaries in this fandom, and I wish I could agree with her, but sadly I do believe there are those in this fandom whose love for Star Wars has been twisted by their worst instincts and their sense of ownership.

Star Wars is far from unique, of course. We live in a nostalgic age, where that sense of ownership has flourished, and social media makes it so easy for some of us to vent. But the worst parts of the fandom are simply like King Canute trying to hold back the tide. Ahmed Best recently illustrated this by recalling how, at the height of the prequel controversy, George Lucas told him the prequel generation would come of age and these films would be loved within 30 years. The controversies of today become the footnotes of tomorrow, and then are forgotten.

Speaking as a Star Wars fan, I quite look forward to that, even if I know there will be yet more controversies tomorrow.